Author Archives: admin

Premiere performance of Climb!

Maria Kallionpää’s new interactive work for piano,

University of Nottingham, 8 June, 5 pm.

Admission free.

Directions: www.lakesidearts.org.uk/about-us/venues.html

Composer and pianist Maria Kallionpää will give the first performance of Climb!, her new interactive work for piano, at the University of Nottingham on June 8th.

Climb! combines contemporary piano with elements of computer games to create a non-linear musical journal in which the pianist negotiates an ascent of a mountain, choosing their path as they go and encountering weather, animals and other obstacles along the way.

Climb! employs the Mixed Reality Lab’s Muzicodes technology to embed musical triggers within the composition. Like hyperlinks, these may transport the player to another point in the score when successfully played, and may also trigger additional musical effects or control visuals. Climb! also uses a disklavier piano which physically plays alongside the human pianist during key passages, engaging them in a human-machine musical dialogue. The interactive score is delivered using The University of Oxford’s MELD dynamic annotated score renderer.

The organisers are also keen to interview people about their experience of the performance. If you are happy with this it would be very helpful if you could quickly sign at: https://nottingham.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/climb-june-8th-2017-mailing-list

The performance is part of the Nottingham Forum for Artistic Research (NottFAR) concert and events series.

Climb! is supported by the EPSRC-funded FAST project (EP/L019981/1).

FAST partners at the ‘Music of Sound’ symposium, 21 April, Oxford

The ‘Music of Sound’ was a 1 day symposium and hack on sonification organised by the University of Oxford e-Research Centre and the Centre for Digital Scholarship.

The theme of the day was sonification, a topic that is inherently interdisciplinary, ranging from digital humanities and data science to sound synthesis, composition and performance. It attracted visitors from all over the country and all around the disciplinary landscape, including several composers and sound artists. You can read the Oxford e-Research Centre news item here.

The FAST project featured in two of the talks, which built on our earlier ‘Numbers into Notes’ work .

Professor De Roure, the FAST IMPACt PI from the Oxford e-Research Centre, presented an update of a short work from 2000 of hypertext fiction based on the traditional (Norwegian) ‘Three Billygoats Gruff’ fairy tale, with sonification of the hyperstructure: given a choice of paths through the story, the reader could listen to an algorithmically generated rendering of the structure beyond each hypertext link. The work later featured in the 2002 conference paper ‘On hyperstructure and musical structure’ and the 2005 workshop paper ‘The Sonification of Hyperstructure‘. Professor De Roure presented a refresh of the work, 17 years on, using contemporary technologies.

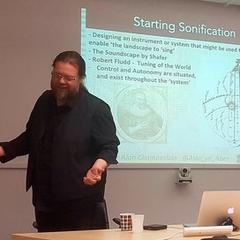

The second talk was presented by the FAST partner from Nottingham, Dr. Alan Chamberlain, and Dafydd Roberts with the title “Between chaos and control: compositional & computational approaches to alchemy inspired sonification”. Chamberlain/Roberts’s work in progress charts compositional and computational approaches to “complex mapping paradigms of [alchemical] data to musical parameters”. Dr. Chamberlain is also a Visiting Academic at the University of Oxford. Below are two compositions that were played at the Symposium and form part of Dr Chamberlain’s research:

Howitzvej Sunset Generative

https://soundcloud.com/alain_du_norde/howitzvej-sunset-generative

FAST in conversation with Gary Bromham, Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London

1. Could you please introduce yourself?

My name is Gary Bromham, I’m a Music Producer, Audio Engineer and Songwriter. I’m also a part-time PhD Researcher at Queen Mary University of London in the Centre for Digital Music. I’m researching the area of retro aesthetics in digital music technology and how they influence music production. Specifically, I’m focused on GUI (Graphic User Interface) design and perception of timbre connected to this area.

2. What is your role within the project?

I have a small advisory role in the project. I suppose my task is to use some of my 30 years of experience to inform on best practices in the field of record production but probably also to act as an arbiter of the usefulness and real world application of new ideas. It’s constructive criticism I suppose!

3. Which would you say are the most exciting areas of research in music currently?

The area of automatic-mixing of multi-track audio interests me greatly. The idea that data gained from observation and analysis of recording and mix engineers can be used to automate mundane and often less creative aspects of this process is very interesting. Labelling of audio tracks based on instrument recognition for example could save huge amounts of time when mixing songs. Streamlining of existing workflows which might facilitate more time for creative processes is a justifiable goal. I am also very interested in the use of semantic technologies for describing sound properties in music production and how they might be a better way for a consumer or hobbyist than a more traditional physics based method.

4. What, in your opinion, makes this research project different to other research projects in the same discipline?

Probably the length of time allotted to the project. This gives time for ideas to evolve and be carried through to a fruitful conclusion rather than merely conceptualized.

5. What are the research questions you find most inspiring within your area of study / field of work?

I’m interested in how tools we use in a more traditional analogue based recording studio can be re-evaluated and re-shaped to work in a digital context. Digital models of hardware are often based on their analogue counterparts, skeuomorphs, this method, quite often, isn’t the best one when used in a computer based music system.

6. What, in your opinion, is the value of the connections established between the project research and the industry?

The industry is very good at knowing what it doesn’t want but less good at knowing what it does want, and needs, for that matter. It is also notoriously slow at embracing new technologies and adapting new ways of working which may be beneficial. Researchers are much better placed to help identify some of the key areas that may assist with speeding up this process. A prime motivation of FAST, for example, is to look at how the production chain might be improved upon. Tracking the path from concept to consumer is a complex one and only by analysing work processes and workflows can we begin to identify what the consumer might benefit from using.

7. What can academic research in music bring to society?

It can help to predict and inform how the production chain might look in the future. Music consumption is largely about convenience not quality these days, but I believe we should aspire to provide a better user experience whist at the same time be offering high resolution audio content.

8. Please tell me why do you find valuable/ exciting / inspiring to do academic research related to music.

I’m not an academic in a traditional sense, but I do have a huge amount of hands-on knowledge and experience to draw upon. Music production is a combination of aesthetics and physics or science and the study of this area needs to be of an interdisciplinary nature if we are to understand and disseminate some of the ‘mystique’ surrounding its history. For this reason, I believe this relatively new field needs to be investigated as thoroughly as possible.

9. Why did you choose this area of research / field of industry?

I’m very interested in why we persist in looking back at retro technologies with an almost obsessional attachment to some kind of holy grail, when we could do things far better by embracing new ways of working. I think it is the duty of a conventional composer or music producer to point this out to both researchers, but maybe more importantly, to manufacturers who often rely on outdated concepts to create tools to facilitate music production processes.

10. What are you working on now?

I’m currently producing an album for a 90’s band called Kula Shaker. I’m also about to run an experiment for my PhD where I’m assessing the effects of GUI design on listeners’ perceptions of audio quality in a DAW.

11. Which is the area of your practice you enjoy the most?

If I’m honest, sitting in front of a mixing desk, but hopefully testing and embracing new hybrid methods of working rather than merely following tradition and relying on familiarity to dictate workflow.

12. What is it that inspires you?

Watching my children write music in ways that we couldn’t conceive of even 10 years ago. The ability to collaborate and share ideas with other like-minded individuals, instantaneously, inspires me greatly.

FAST in conversation with Florian Thalmann, Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary

- Could you please introduce yourself?

I grew up in Switzerland in a both musical and scientific environment. During my Computer Science studies at the University of Bern, I became increasingly interested in theoretical aspects of music and music history and attended musicology classes in my free time. After my studies, I gained some experience in the industry working as a software engineer, while also frequently performing as a musician. When I was offered a PhD position that allowed me to combine my two primary passions, I decided to go back to academia. I spent the following years at the University of Minnesota to pursue a PhD in Music Theory. After my studies, I joined the Centre for Digital Music and the FAST project as a postdoctoral researcher at Queen Mary in London.

- What is your role/work within the project?

Within FAST I’m mainly concerned with the consumption side of things, particularly with enabling new kinds of experiences during music discovery and music listening. I’m working on new ways of automatically analyzing music and representing it in a semantically annotated and flexible way so that it can be compared, browsed, and played back nonlinearly, i.e. dynamically reorganized to adapt to the listener’s context or respond to user interaction. I’m involved in various research and artistic collaborations within the project and beyond, where these technologies are being tested and used creatively.

- What, in your opinion, makes this research project different to other research projects in the same discipline?

The FAST project is highly interdisciplinary and unites three research groups with very different but complementary specializations, which nurtures our equally interdisciplinary goals by bringing together signal processing, studio technology, the semantic web, artificial intelligence, workflow analysis, ethnography, and design. We are possibly the only project considering the entire value chain of the music industry, from composition, via recording, production, and distribution, to consumption. One of our main goals, using linked data to enable a musical entity to travel through the entire music value chain while accumulating more and more information that will be useful at various stages, can only be achieved through the collaborative work of people with such varied and creative backgrounds, as well as with our industrial partners.

- What are the research questions you find most inspiring within your area of study / field of work?

With my background in music theory, I’m thrilled by the possibilities of automatically analyzing large collections of musical material and, for instance, finding trends and long-term developments in a particular artist’s or group’s work, similarities and connections with other artists, or differences in how a work is performed on different days and/or in different environments.

From the point of view of education, I’m interested in enabling music discovery and teaching through music listening itself, e.g. by highlighting particular musical aspects directly within the audio, instead of using distracting and abstract visualizations detached from the musical content. I’m also interested in educational and creative uses of sonification in order to, for example, present results of search queries in an auditory way.

As a performer, I’m mainly interested in coming up with new ways of interacting with musical material using physical and gestural interfaces, while trying to match the versatility of traditional graphical and textual computer interfaces. From this perspective, the use of machine learning in realtime is particularly interesting, for I’ve found that such systems often behave in unpredictable, seemingly creative ways.

- What, in your opinion, is the value of the connections established between the project research and the industry?

It’s a great opportunity to not only discuss the interests and requirements of our industry partners first-hand, but also improve our outreach by implementing prototypes in collaboration with our partners, which could then be further developed for specific applications in the industry. Sometimes new developments in the industry can be difficult to oversee and they often remain concealed until they are launched publicly. It’s therefore very valuable to have our ideas scrutinized at an early stage and from an economic point of view by our partners.

- What can academic research in music bring to society?

Musical practice has always been surprisingly quick to embrace new technological developments, both in experimental circles and the mainstream. Many technological ideas emerge and are first elaborated in academic contexts, to then be applied in practice and distributed in an economic context, e.g. by startup companies. These, in turn, make it possible for new musical tools and devices to become accessible and affordable by a larger audience of musicians and consumers, who almost always use the technology in creative ways that were initially not envisioned. It’s very exciting to see this process.

Besides having a potential technological influence on the music of the future, perhaps more importantly, academic research can further the understanding of our incredibly rich musical heritage. Research not only contributes to our common knowledge about music, but it can help to organize existing musical knowledge and public music collections and make them accessible and understandable by a large community of musicians, students, researchers, and music lovers. These aspects are of course equally relevant to the music industry who may find new ways of recommending and distributing music, as well as creating new experiences.

- What are you working on now?

I’m currently working on pattern recognition algorithms and music similarity models that allow us to automatically recognize and analyze various kinds of musical form and structure. I’m also working on finding appropriate ways to represent such musical structures as semantically annotated hierarchical and graph-based structures so that they can be queried, compared, and navigated. These algorithms and models are being applied in several projects within FAST.

For example, we’re looking at the Grateful Dead collection in the Live Music Archive, an incredibly valuable collection of live recordings from the early days of the group in the sixties to its disbandment in the mid-nineties. We are using the algorithms on various subsets of the collection. For example, we align different tape recordings of a single concert, spatialize them, and create an immersive experience in which the listener can move around. We also compare different performances of the same song across decades and allow listeners to move through time while listening to a song.

We’re also working on reorganizing and transforming recordings of various nature. We first decompose the recordings into single sound events using source separation algorithms and then put these sounds back together dynamically. This enables us to do things such as spatialize the contents of a mono recording around the listener to highlight some musical aspects or distort a recording in time to zoom in on certain performance aspects.

As a foundation of all this, I’m building a prototype of a mobile and web-based player, the Semantic Player, which uses these algorithms and representations to find out how any provided musical material can be played back in a malleable and dynamic way. The player can receive any input from mobile device sensors and data from the web, which can then be used to modify the music. We’re currently experimenting with all kinds of experiences where, for instance, the music adapts to contextual conditions such as the weather at the listener’s current location.

- Which is the area of your practice you enjoy the most?

I really enjoy thinking about specific problems and trying to come up with solutions that can then be generalized to other problems or situations. I also enjoy discussing problems with other researchers and collaborating to try to bring together different parts of research in a common application. In FAST, we are experiencing this all the time when working on our joint demonstrators. Most importantly, I’m almost always driven by an idea of something I would like to use or listen to myself. Nothing is more satisfying to me than implementing a new methodology and testing it experimentally, playing around with it, or even performing with it, and then improving and optimizing it iteratively.

- What is it that inspires you?

A lot of my inspiration comes from other disciplines and thinking about how they connect. I love creating analogies between situations in another field of application and the one I’m currently concerned with. There is always someone that has tried similar things before, however their work can easily be overlooked if it was conducted in a different field, so bridging the gap between research in different disciplines is important. Most importantly, I get a lot of inspiration from musical practice, nature, and the arts in general.

A. Blumlein to be honoured with Technical Grammy award

Alan Dower Blumlein, the British engineer and inventor of stereo sound recording, is to be posthumously honoured by the Recording Academy in the USA with the Technical Grammy award, according to the Engineering & Technology Magazine.

Speaking about the Grammy recognition to E & T, Simon Blumlein, Alan Blumlein’s son, said: “It is a great honour for my father and the Blumlein family to be recognised with such a prestigious award. We’re so immensely proud of him and how his work transformed sound recording. He’s always been held in the highest esteem by recording engineers and so to now receive this acknowledgement from the wider music industry is simply wonderful.”

Speaking about the Grammy recognition to E & T, Simon Blumlein, Alan Blumlein’s son, said: “It is a great honour for my father and the Blumlein family to be recognised with such a prestigious award. We’re so immensely proud of him and how his work transformed sound recording. He’s always been held in the highest esteem by recording engineers and so to now receive this acknowledgement from the wider music industry is simply wonderful.”

The E & T article in full can be read here.

FAST partners contribute to new book on ‘Mixing Music’

Mixing Music (eds: Russ Heptworth-Sawyer & Jay Hodgson), Perspectives on Music Production series, New York / Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

The series, Perspectives On Music Production, collects detailed and experientially informed considerations of record production from a multitude of perspectives, by authors working in a wide array of academic, creative, and professional contexts. The editors solicit the perspectives of scholars of every disciplinary stripe, alongside recordists and recording musicians themselves, to provide a fully comprehensive analytic point-of-view on each component stage of record production. Each volume in the series thus focuses directly on a distinct aesthetic “moment” in a record’s production, from pre-production through recording (audio engineering), mixing and mastering to marketing and promotions. This first volume in the series, titled Mixing Music, focuses directly on the mixing process.

The series, Perspectives On Music Production, collects detailed and experientially informed considerations of record production from a multitude of perspectives, by authors working in a wide array of academic, creative, and professional contexts. The editors solicit the perspectives of scholars of every disciplinary stripe, alongside recordists and recording musicians themselves, to provide a fully comprehensive analytic point-of-view on each component stage of record production. Each volume in the series thus focuses directly on a distinct aesthetic “moment” in a record’s production, from pre-production through recording (audio engineering), mixing and mastering to marketing and promotions. This first volume in the series, titled Mixing Music, focuses directly on the mixing process.

Gary Bromham, a member of the FAST team from Queen Mary University of London, contributed a chapter entitled “How Can Academic Practice Inform Mix-Craft?”. According to Bromham, the democratisation of music technology has led to a stark change in the way we approach music production and specifically the art of mixing. There is now a far greater need for an understanding of the processes and technical knowledge a mix engineer, both amateur and professional, needs to execute their work practices. Where the intern once learned their craft from assisting the professional in the studio, it is now more commonplace for them to learn from a book, an instruction video or within a college or university environment. As Paul Théberge suggests, explains Bromham, there is a ‘lack of apprenticeship placements’ (Théberge 2012). Unlike the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, these days anyone can make a record, quite often working remotely and increasingly using headphones rather than speakers, and in many cases, using spaces that weren’t designed to be studios. We use sound libraries, plugin presets and templates and in doing so create the illusion that an understanding of how we arrive at the finished sound isn’t necessary. Technology gives us infinite options and possibilities but in doing so often stifles creativity and inhibits decision-making. There is a feeling that we are using the technology without understanding it. Bromham advances that it is therefore more important than ever that the student and practitioner alike learn how to approach mixing with some grounded theory and scientific knowledge. The DAW and the project studio have become ubiquitous yet they are metaphors for the traditional recording studio. Academic research practices such as ethnographic studies, scientific evaluation and auditory analysis (acoustic and psychoacoustic) can all greatly assist the understanding of the mix engineer’s craft. How can we learn from aesthetical, musicological, historical and scientific studies and apply them to a contemporary studio workflow?, asks Bromham.

Two other members of the Queen Mary FAST team, Mathieu Barthet and George Fazekas also contributed to Bromham’s piece by way of interview. They namely stressed on the importance of multidisciplinary perspectives on mixing and the use of human computer interaction design methods to transform creative agency in the digital audio workstation.

Gary Bromham is now conducting PhD research supervised by George Fazekas, Mathieu Barthet and Marcus Pierce, looking into how technology influences music production practice and musical aesthetics.

The book Mixing Music includes:

- References and citations to existing academic works; contributors draw new conclusions from their personal research, interviews, and experience.

- Models innovative methodological approaches to studying music production.

- Helps specify the term “record production,” especially as it is currently used in the broader field of music production studies.

FAST in conversation with Adrian Hazzard, University of Nottingham

in August 2016, FAST interviewed Dr Adrian Hazzard, one of the FAST partners from Nottingham about the FAST project.

- Could you please introduce yourself?

I’m Adrian Hazzard, a Research Fellow at the Mixed Reality Laboratory, University of Nottingham. - What is your role within the project?

I’m a full-time researcher developing and evaluating research projects within the FAST project. - Which would you say are the most exciting areas of research in music currently?

For me it is the creative possibilities that the intersection between music production / performance and digital technologies, in particular web-based and context-aware technologies offer. Web based tools are essentially pervasive across all our everyday digital interactions and this is very much the case with music consumption, you just have to think of Spotify and YouTube. However, we are now increasingly seeing web-based tools seeping into the realm of music production, they offer uniformity, access, sharing and integration with other media on a scale not previously possible. If you then add in approaches such as ‘adaptation’ and ‘augmentation’, where music can adapt or respond in real-time to contextual information, then the future of music listening seems very broad and exciting. We seem to be at a bit of tipping point between the traditional analogue recording studio paradigm, which has formed the design of digital workstations to date and new technologies that may stretch beyond into new paradigms of interaction and consumption. - What, in your opinion, makes this research project different to other research projects in the same discipline?

The FAST project is unique on several levels. As a long-term project (5yrs) it enables for a deep exploration and development of new approaches into music production and consumption that would not be possible on shorter-term research engagements. The academic team consisting of Queen Mary, University of London, University of Oxford and University of Nottingham bring together a diverse, but complimentary set of knowledge and skills and there is a broad range of industry partners who are active in shaping and guiding the projects research agenda. Collectively, these attributes enabled the project to (initially) set out with a broad remit of research: to explore and experiment into many diverse areas of music production and consumption, this has now led to a focusing on a few core areas. - What are the research questions you find most inspiring within your area of study?

I find inspiration in ‘how the composition and production of music can be enhanced and shaped by contemporary digital tools’ and then ‘what do these new forms of musical experience mean for the listener’. - What, in your opinion, is the value of the connections established between the project research and the industry?

The industry connections on the FAST project have been an essential foil for a number of reasons. This research project aims for a significant industry impact, so it is imperative that as an academic team we are sensitive to the current state of the industry, to recognise the challenges and the opportunities at play. Our industry connections give us a unique insight into many areas of the music industry, such as the world traditional recording studios (Abbey Road), and the broadcast industry (BBC). Second, our industry team provide a mentoring and advisory role, from which we can gather constructive criticism of our research directions and outputs. - What can academic research in music bring to society?

Most people engage with music in some form on a daily basis. This might be as entertainment such as listening to music on the radio, a HiFi system or a mobile device; or as part of a formal service or ceremony; or as an accompaniment to a television programme, film or computer game – music is one of the most pervasive media types and it forms an integral part of many of our everyday formal and informal experiences. In short, music is important to society and therefore it is important to understand its role and impact, as well as to explore, and push at, its boundaries. While musical artists, with support from ‘the industry’ are the creative force behind the music we listen to, academia can play a vital role in distilling how music ‘works’ and how technologies can continue to support new creative endeavours, whether in music production or in other disciplines. - Why did you choose this area of research?

My career to date has, in some form or other, revolved around music. I’ve previously worked as a performer, composer and music teacher across a number of settings. I came into academia later on in life and this has offered me a new and exciting opportunity to play some (very small) part in capturing and charting the development of new musical approaches and experiences… what could be better than that! - What are you working on at the moment?

Currently, I’m working on a project called Muzicodes, a web-based music feature recognition system for performers. The system enables an instrumentalist(s) to trigger performance media by playing pre-defined melodic or rhythmic fragments; essentially musical ‘codes’. The performer identifies points in a musical work where they may want to trigger a backing track, or a MIDI event, or a lighting or visual cue of some description. The musical fragment or sequence that is played at point in the music then becomes the trigger for that action. There is an interesting challenge between creating a ‘code’ that is both suitable for the musical work and consistently recognisable by the system. - Which is the area of your practice you enjoy the most?

That’s a tricky question, as I enjoy many different aspects of this practice. For instance, I particularly enjoy the generation of research ideas, bouncing them off different people or reading something that inspires and leads you to the formation of a particular idea. Having said that, the following realisation of a research idea or ‘thing’ is equally exciting, although sometimes they are accompanied by a healthy frustration of seeing what they could have been given more time, resources and skill. - What is it that inspires you?

Any creative musical interaction, whether it is a great composition or a musical expression on an instrument performed with conviction.

FAST in conversation with David Weigl, Oxford University

in August 2016, FAST interviewed Dr David Weigl, one of the FAST partners from the Oxford e-Research Centre, Oxford University about the FAST project.

in August 2016, FAST interviewed Dr David Weigl, one of the FAST partners from the Oxford e-Research Centre, Oxford University about the FAST project.

1. Could you please introduce yourself?

I’m originally from Vienna, Austria. I moved to Scotland when I was 18, where I studied at the University of Edinburgh’s School of Informatics, and played bass in Edinburgh’s finest (only!) progressive funk rock band. After a few years in industry, I decided to return to academia to combine my research interests in informatics and cognitive science with my passion for music, pursuing a PhD in Information Studies at McGill University. Montreal is an amazing place to conduct interdisciplinary music research; at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology (CIRMMT), I was able to collaborate directly with colleagues in the fields of musicology, music tech, cognitive psychology, library and information science, and computer science, while benefiting from even more diverse perspectives, from audio engineering to intellectual property law. For the past couple of years, I’ve had the pleasure of working at the University of Oxford’s e-Research Centre, an even more interdisciplinary place: here at the OeRC, researchers supporting Digital Humanities projects regularly exchange notes with projects down the hall in radio astronomy, bio-informatics, energy consumption, and climate prediction.

2. What is your role within the project?

My role in the FAST project revolves around the application of semantic technologies and Linked Data to music information, in various forms: from features describing the audio signal extracted from live music recordings, via symbolic music notation, to bibliographic information, including catalogue data and digitized page scans from the British Library and other sources. The projects I work on support complex interlinking between these musical resources and tie in external contextual information, supporting rich, unified explorations of the data.

3. Which would you say are the most exciting areas of research in music currently?

Research into music information retrieval (MIR), and related areas of study, has been on-going since the turn of the millennium, when digital affordances, technologies such as the MP3 format, and widespread adoption of the Internet suddenly made digital music information ubiquitously available. The music industry took a long time to respond to the corresponding challenges and opportunities, but products such as Spotify, Pandora, and YouTube are now reaching a level of maturity enabling exciting new avenues of music discovery. Yet we are only listening to the tip of the iceberg, as it were. Many powerful techniques developed by the MIR community have not yet been exploited by industry; as we see more and more of these research outcomes integrated into user-facing systems, new ways of listening and interacting with music will become available.

4. What, in your opinion, makes this research project different to other research projects in the same discipline?

The cross-disciplinary, multi-institutional nature of the project, bringing together collaborative research into digital signal processing, data modelling, incorporation of semantic context, and ethnographic study across all stages of the music lifecycle, from production to consumption – combined with a long-term outlook, seeking to predict and inform the shape of the music industry over the coming decades – make FAST a particularly exciting project to be involved in!

5. What are the research questions you find most inspiring within your area of study?

I am especially interested in the notion of relevance when searching for music. This seems like such a simple notion when searching for a particular song – either the retrieved result is relevant to the searcher, or it isn’t – but the resilience of musical identity, retained through live performances, cover versions, remixes, sampling, and quotation, swiftly makes things more complicated. Deciding what is relevant becomes even more difficult when the listener is engaging in more abstract searches, e.g. for music to fulfil a certain purpose. For example, what makes a great song to exercise to? Presumably, some aspects – liveliness, energy, a solid beat – are universal, yet the “correct” answer will vary according to the listener’s expectations, listening history, and taste profile – be it Metallica, Daft Punk, or Beethoven.

6. What, in your opinion, is the value of the connections established between the project research and the industry?

I think such connections are valuable for numerous reasons. From the academic side, access to industry perspectives allows us to validate our assumptions about requirements and use cases; application of academic outputs within industry further acts as a sort of impact multiplier, ensuring our results are applicable to the real world. For industry, the value is in exposure and access to the latest state of research, fuelled by transparent, multi-institutional collaboration.

7. What can academic research in music bring to society?

On the one hand, advances in music information research have allowed us to conquer the flood of digital music available through modern technologies, enabling efficient and usable storage and retrieval. Each of us carries the Great Jukebox in the Sky in our pockets; listeners are able to access incredibly vast quantities of music wherever and whenever they like, and are better equipped than ever to inform themselves about the latest releases, and to discover hidden gems to provide a perfect fit for their taste and situation. Musicologists are able to subject entire catalogues to levels of scholarly analysis previously reserved for individual pieces, and are able to cross-reference between works by different composers, from different time periods or cultures, with such ease that the complexity of the interlinking fades into the background, becoming barely noticed.

On the other hand, such research has democratised music making and music distribution, providing artists with immediate access to their (potential) audience. Academia and industry must collaborate to ensure that monetisation is similarly democratised, to protect and strengthen music composition and performance as a viable career path for talented and creative individuals.

8. Please tell me why do you find valuable to do academic research related to music.

I’m very fortunate in that I get to combine my academic interests with my personal passion for music. I think that every researcher in the field feels this way; everybody I talk to at conferences plays an instrument, or sings, or produces music in their spare time. Music is inherently exciting – when I’m asked about my research at a social gathering, and I answer “information retrieval,” “linked data,” or “cognitive science”, I get a polite nod of the head; when I answer that I work with music and information, people’s eyes light up!

9. What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on a number of different projects combining music with external contextual information using Linked Data and semantic technologies.

I have developed a Semantic Alignment and Linking Tool (SALT) that supports the linking of complementary datasets from different sources; we’ve applied it to an Early Music use case, combining radio programme data from the Early Music Show on BBC Radio 3 with library catalogue metadata and beautiful digitised images of musical score from the British Library, enabling the exploration of the unified data through a simple web interface.

I’m also working on the Computational Analysis of the Live Music Archive (CALMA), a project that enables the exploration of audio feature data extracted from a massive archive of live music recordings; for instance, we have access to hundreds of recorded renditions of the same song by the same band, performed over many years and at many different venues, allowing us to track the musical evolution of the song over time and according to performance context – does the song’s average tempo increase over the years? Do the band play more energetically in-front of a home crowd?

Finally, I’ve recently presented a demonstrator on Semantic Dynamic Notation – tying external context from the web of Linked Data into musical notation expressed using the Music Encoding Initiative (MEI) framework. This technology supports scholarly use cases, such as direct referencing from musicological discussions to specific elements of the musical notation, and vice versa; as well as consumer-oriented use cases, providing a means of collaborative annotation and manipulation of musical score in a live performance context.

10. Which is the area of your practice you enjoy the most?

The best parts are when multiple, disparate data sources are made to work together in synergistic ways, and unified views across the data are possible for the first time. This provides real “aha!” moments, where the hard data modelling work pays off, and complex insight becomes available.

Mixing for mundane everyday contexts

by Sean McGrath (The University of Nottingham)

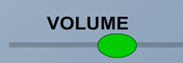

Recent endeavours at the Mixed Reality Lab at Nottingham have explored the use of mixing in consumer audio. As technology becomes more pervasive, consumers now have substantially more options in their choice of listening experiences. We aim to explore the role of volume in multi-track audio and to ascertain to what degree control over audio features can benefit users in their everyday listening experiences.

The research is driven by the following questions:

- Can non-optimal audio be mixed in an optimal way? How do users reason about this?

- Do these additional controls afford additional utility and if so, how might they improve the user experience?

- How does context define the level of control, access and utility in this scenario?

The work utilises a technology probe developed by Dr Sean McGrath at the MRL. The probe is a simple web-based application that pre-loads a series of multitrack components and randomises the order in which they are played. This enables the representation of both optimised and non-optimised mixes where repetition of tracks is possible. For instance, a listener may be presented with four distinctive instrument tracks, four identical drum tracks or some permutation between. The interface offers no way of knowing what mix is present, other than by adapting volume controls to try to ‘discover’ the configuration in place.

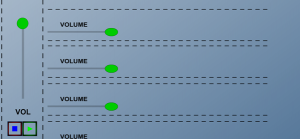

Figure 1 – Controls on the interface display current volume, master audio volume control and individual track audio controls.

The tool has been placed in a variety of different settings, at home and at work. Here we aim to mimic listening habits, relying on familiar hardware and environments, with the tool a centrepiece of this. The hybrid mix of a new tool embedded in existing setups presents context-driven problems and solutions. The focus is on adding utility and control and better understanding how we can build malleable music listening experiences for future audiences and contexts.

User feedback has placed the tool into a number of useful contexts, alluding to places where implantation of such controls would or could be beneficial. There has also been feedback about how the tool could be adapted for different contexts, such as in the car or in a shared space. The work has encompassed the social element of music listening, looking at how groups engage with the tool in socially rich settings and exploring the use of the tool in mitigating factors such as control, access and expression. The work is currently being written up as a paper.